The protective factors for mental health inherent to Career Technical Education (CTE) may offer opportunities to improve mental health and overall outcomes for learners, solidifying CTE’s role in not only preparing learners for the workforce but also for life. In the final installment of this four-part blog series, Senior Communications Associate and Mental Health Educator Jodi Langellotti uses research on hope and messaging to provide examples and tips for CTE leaders to incorporate CTE’s role in protecting youth mental health into recruitment and program communications.

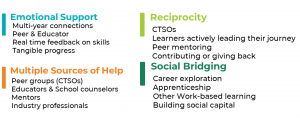

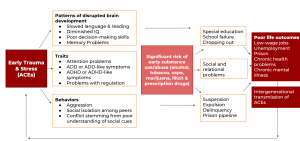

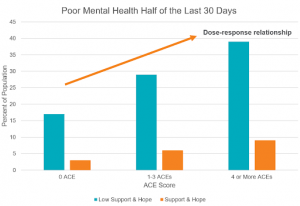

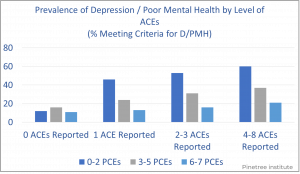

In the previous blogs in this series, we discussed how 80% of our most common health, social, and behavioral challenges are a direct result of trauma experienced in childhood which causes developmental changes in the brain that can result in challenges with focus, attention, emotional regulation, executive functioning skills, and more. Positive childhood experiences (PCEs) or protective factors such as having two caring adults outside of the home and experiencing a sense of belonging in school and the community can buffer the negative effects of childhood trauma. The activities within CTE foster hope, support, and developmental relationships and therefore serve as a protective factor for mental health. CTE is preparing learners for their future outside of the classroom, in the workforce, and for life.

Messaging the Role of CTE as a Protective Factor

Messaging CTE is marketing CTE to current and prospective learners and families to increase enrollment, retention, and completion. One of the foundational principles of marketing strategy includes creating messages that resonate with the audience by connecting to their values, and needs, and through their preferred channels of communication. It is important for state and local CTE leaders to directly engage with the intended audience (learners and families) in order to learn about their values, needs, and communication preferences. The following research and examples for messaging CTE as a protective factor for mental health should be considered a starting point and should be tailored to best meet the needs of the intended, specific audience.

Hope

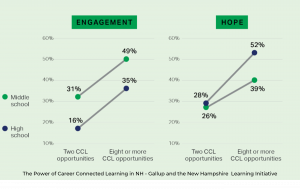

Research has shown that hope and engagement have a positive relation to student achievement and their likelihood to graduate.1 Additional research has shown that hope has a significantly positive impact on anxiety, depression, and academic performance.2

Charles R. Snyder, PhD, a former psychologist at the University of Kansas and a pioneer of hope research created a model of hope with three components: goals, agency, and pathways. Agency is the belief that one can shape their own life, “make things happen” and access the motivation to reach their goals. Pathways are the routes and plans that allow one to achieve an established goal.3

To help connect hope to CTE recruitment and program messaging, state and local leaders can lean into the components of their programs that help to nurture the three tenets of hope Snyder outlined – goals, agency, and pathways.

In the examples above emphasis is placed on “you” and “your” to help connect to the idea that it is the learner who is building their future and creating their path (agency). Words like “create”, “design”, and “build” connect to both the concept of agency and pathways (how they will get there). In all three examples the word “future” is used to help connect to the individual goals that a learner may have.

Making Connections

Messaging research conducted by Advance CTE with the support of Siemens Foundation shows that “making connections” is a strong retention message and is desired among prospective learners, especially Black, Latinx, and learners experiencing low income. Additionally, there is a correlation between poor social connections, poor mental health, and substance abuse.4 Addiction specialists cite a lack of social connection as a primary risk factor for substance use disorders.5

CTE provides numerous opportunities for learners to connect to their peers, educators, and industry professionals. Recruitment and program messaging can lean into the idea of “making connections” to help learners and families become more aware of this aspect of CTE.

In the examples above emphasis has been placed on the idea of connection through the professional networking, people, skills, and community that learners are exposed to in CTE.

Feeling Prepared for the Future

According to ECMC Group’s “?uestion the Quo” research, only 13% of Gen Z teens surveyed feel fully prepared to choose their path after high school, “The areas where they seek additional information include finances (such as guidance on future debt and managing unexpected costs), education and career pathways, health (such as guidance on mental and physical health support) and logistics (such as housing).”6

In both 2017 and 2020, Advance CTE found that 60% of prospective and current CTE families chose “Preparing for the real world” as the most important aspect of CTE. The 2024 CTE perception survey conducted by Advance CTE and Edge Research showed that the statement “Be prepared for the real world” still resonates as motivating and extremely motivating with learners and families. Interestingly, however, the statement “Gain skills and experience that lead to financial security and independence” ranked the highest among all respondents.

While the perceptions survey research has just two years for comparison, Advance CTE’s previous messaging research and additional research such as ?uestion the Quo clearly show that families and learners are thinking about the skills and experiences they need to be prepared for the future.

In the examples above, emphasis has been placed on the ability of CTE to help learners feel prepared for their future and achieve financial security.

Next Steps and Recommendations

This blog series has served as a starting point for the conversation around how the inherent aspects of CTE serve as a protective factor for youth mental health and as a contributor to positive learner outcomes. To move this conversation forward and into state and local systems, the following actions are recommended for state and local CTE leaders:

- Engage with learners and families to determine how current recruitment and program messaging, or the provided examples, connect to their values, needs, and preferences. To learn more about engaging learner voice, check out With Learners, Not For Learners: A Toolkit for Elevating Learner Voice in CTE

- Consider who in the state, district, institution, or team is already thinking about learner mental health and the connection to positive outcomes. These may be school counselors and psychologists, community leaders, and partner organizations. Engage these collaborators in conversations about CTE’s role as a protective factor for youth mental health.

- Collect stories and data from learners and families on the positive impact of CTE on their hope for their future, their engagement in school, and their academic performance. Consider how to add questions to existing data tools and collection methods and partner with school counselors, community leaders, and partner organizations to collect this information.

Additional Resources

- Mission impossible: Being hopeful is good for you. Weir, Kirsten, American Psychological Association, October 2013, Vol 44, No. 9: https://www.apa.org/monitor/2013/10/mission-impossible

- The Power of Career Connected Learning in NH: https://nhlearninginitiative.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Gallup-New-Hampshire-Learning-Initiative_-Report_2023.pdf

- Engaging Learners and Families: Advance CTEs messaging research and work funded by the Siemens Foundation. https://careertech.org/what-we-do/case-making-communications/engage-families-learners/

Much of the information in this blog is from the author’s training as an Adverse Childhood Experiences Master Trainer through ACE Interface with Dr. Robert Anda and Laura Porter and through her volunteer work within the community mental health space.

Much of the information in this blog is from the author’s training as an Adverse Childhood Experiences Master Trainer through ACE Interface with Dr. Robert Anda and Laura Porter and through her volunteer work within the community mental health space.

Jodi Langellotti, senior communications associate