Workforce readiness takes center stage in most education policy conversations these days. With last year’s reauthorization of the Carl D. Perkins Career and Technical Education Act of 2006 (now known as the Strengthening Career and Technical Education for the 21st Century Act or Perkins V), state leaders are increasingly focused on how they can improve and increase access to high-quality career technical education (CTE) programs. With more attention being paid to this important work, state leaders must be transparent about which kinds of CTE programs are being offered, who is accessing them, and how participants fare once they’re finished. To do this, states need to collect data that is meaningful and share it in ways that people can access and use to make informed decisions. Unfortunately, CTE data currently available leaves most students and families in the dark.

According to a recent report from Advance CTE in collaboration with partners including Data Quality Campaign (DQC), less than half of State CTE Directors say their CTE data systems provide the information needed to assist in making decisions about program quality and initiatives at both the secondary and postsecondary levels. The majority of states report being able to collect learner-level data on a variety of career readiness measures at the secondary level, but for a variety of reasons this information isn’t found on states’ most public-facing resource about school quality, their school report card.

In January 2019, DQC reviewed every state’s report card and found that only 21 states included the number or percentage of students who completed a CTE program or earned an industry credential. Almost no state reported a separate graduation rate for CTE concentrators. How states chose to report this information also varied greatly, making it difficult at times to understand and interpret the data. Some states reported CTE certification rates as a standalone indicator, while others rolled it into a broader college and career readiness (CCR) indicator. Combined CCR indicators are simple (in theory) but often contain a variety of very different data points (such as CTE certifications earned, dual enrollment, and AP course completion rates) and that summary indicator is rarely broken out to give readers a clear picture of the outcomes for each of the included, and very different, measures.

Two states, South Carolina and Pennsylvania, stood out for the variety of data each include about students’ pathways, which DQC highlighted as bright spots. South Carolina reports detailed CTE data, including course enrollment and completion, credential attainment, and the types of industry credentials earned by Career Cluster® (e.g., Business Management & Administration, Finance, etc.). Pennsylvania includes data about postsecondary pathways more broadly, such as military enlistment and postsecondary enrollment rates disaggregated by student group, as well as the percentage of students who have completed a work-based learning experience.

It’s certainly a positive step forward to see almost half of states beginning to include CTE data on their report cards, but more state leaders need to follow suit. By including CTE and career readiness data side-by-side with college-going rates, state leaders can help students and families see the value of CTE pathways. As states invest significant resources into further developing CTE programming, it is critical that they be transparent about program participation and student outcomes. In order for students to utilize these programs as paths to better outcomes, they must be equipped with the data needed to guide them there.

This is a guest blog post from Elizabeth Dabney, Director of Research and Policy Analysis at the Data Quality Campaign. The post was originally published here.

How many girls of color earned an industry-recognized credential in Information Technology last year? What types of work-based learning experiences lead to the best wage outcomes for learners from low-income families? How many graduates from Career Technical Education (CTE) programs in advanced manufacturing go on to work in their field of study?

How many girls of color earned an industry-recognized credential in Information Technology last year? What types of work-based learning experiences lead to the best wage outcomes for learners from low-income families? How many graduates from Career Technical Education (CTE) programs in advanced manufacturing go on to work in their field of study? Ensuring learners are prepared with the skills and experiences they need for high-wage, high-skill employment in in-demand occupations is a shared responsibility among secondary education, postsecondary education and the workforce sector. Yet too many states continue to use disparate data systems for collecting, validating and accessing learner-level data. Using disparate systems not only increases the data collection burden for local leaders but also threatens the quality of the data and the ability of state leaders to use their data effectively.

Ensuring learners are prepared with the skills and experiences they need for high-wage, high-skill employment in in-demand occupations is a shared responsibility among secondary education, postsecondary education and the workforce sector. Yet too many states continue to use disparate data systems for collecting, validating and accessing learner-level data. Using disparate systems not only increases the data collection burden for local leaders but also threatens the quality of the data and the ability of state leaders to use their data effectively. In a strong signal of support for Career Technical Education (CTE) and career readiness in high school, 40 states are now measuring career readiness in their state or federal high school accountability systems. Fewer than half as many – 17 – were measuring career readiness just five years ago.

In a strong signal of support for Career Technical Education (CTE) and career readiness in high school, 40 states are now measuring career readiness in their state or federal high school accountability systems. Fewer than half as many – 17 – were measuring career readiness just five years ago. Another commonly used measure is Progress Toward Post-High School Credential. Seventeen states and the District of Columbia include measures aligned with the Destination Known recommendations, and another 22 states include out of sequence indicators. A number of states include either pathway completion or dual enrollment coursework in their accountability plans without requiring that experience to be accompanied by the completion of a state-defined college- and career-ready course of study, which is the Fundamental measurement in this category.

Another commonly used measure is Progress Toward Post-High School Credential. Seventeen states and the District of Columbia include measures aligned with the Destination Known recommendations, and another 22 states include out of sequence indicators. A number of states include either pathway completion or dual enrollment coursework in their accountability plans without requiring that experience to be accompanied by the completion of a state-defined college- and career-ready course of study, which is the Fundamental measurement in this category. The answer is, it’s complicated. According to the

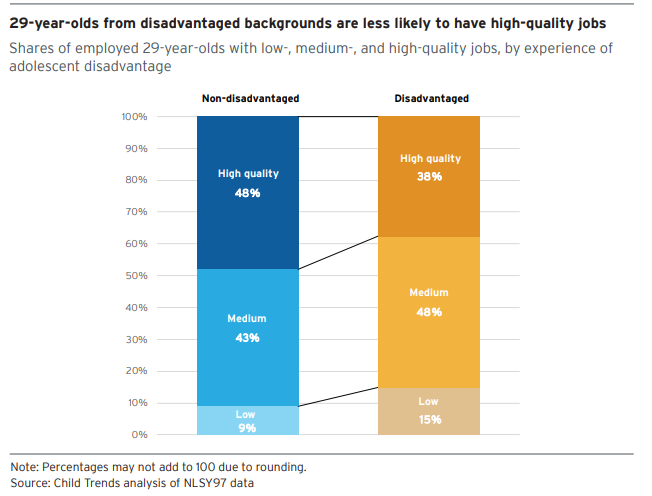

The answer is, it’s complicated. According to the  Specifically, the researchers find that participating in “relationship-focused CTE” (a term they use to refer to work-based learning and other activities where students interact with industry mentors) is significantly related to higher job quality scores at age 29. This would seem to suggest that building relationships with industry mentors and completing work-based learning at an early age can help learners, particularly low-income learners, get a leg up on their careers. While the data do not provide a full picture of the quality of work-based learning in the study, the evidence is promising.

Specifically, the researchers find that participating in “relationship-focused CTE” (a term they use to refer to work-based learning and other activities where students interact with industry mentors) is significantly related to higher job quality scores at age 29. This would seem to suggest that building relationships with industry mentors and completing work-based learning at an early age can help learners, particularly low-income learners, get a leg up on their careers. While the data do not provide a full picture of the quality of work-based learning in the study, the evidence is promising.  The document notes that, despite an abundance of initiatives and efforts, our nation is not achieving its goals in preparing students for college majors or careers in STEM and offers three main principles to drive and implement outstanding STEM education research and practices:

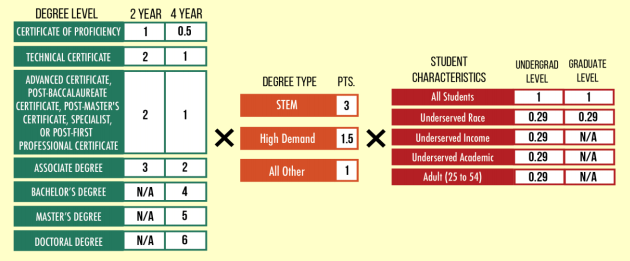

The document notes that, despite an abundance of initiatives and efforts, our nation is not achieving its goals in preparing students for college majors or careers in STEM and offers three main principles to drive and implement outstanding STEM education research and practices: The points an institution receives in the formula for credential attainment are multiplied if the credentials are in Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM) or state-defined “high-demand” fields. Qualifying fields are designated by the the Arkansas Department of Higher Education and the Department of Workforce Services. The multiplier for STEM degrees is 3 points; the multiplier for degrees in high-demand fields is 1.5 points.

The points an institution receives in the formula for credential attainment are multiplied if the credentials are in Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM) or state-defined “high-demand” fields. Qualifying fields are designated by the the Arkansas Department of Higher Education and the Department of Workforce Services. The multiplier for STEM degrees is 3 points; the multiplier for degrees in high-demand fields is 1.5 points.